|

| Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab |

‘But Faith, like a jackal, feeds among the tombs, and even from these dead doubts she gathers her most vital hope.’

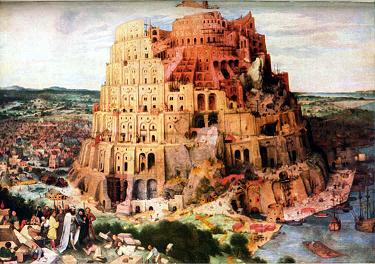

It is an arresting image. To describe Faith in such graphic and fleshly, if not downright menacing terms leaves me wondering about the nature of Melville’s faith and the nature of my own. There is a temptation to think we know definitively what certain words actually mean. We even have the temerity to think this about theological or metaphysical words. The truth is that very often we are simply winging it or, to change the metaphor, we are paddling at the edge of a vast ocean of meaning. Take the word, Truth, for example. Pontius Pilate is often portrayed (perhaps understandably) as the nasty character at the trial of Jesus of Nazareth. But at one point, in response to a comment of Jesus, Pilate asks the question: ‘What is Truth?’ (John 18:38). Pilate has, in some quarters, never been allowed to live that one down. He has become in the minds of these folk a kind of whipping boy, who represents all that is wrong with relativistic, woolly or simply lazy thinking. I think that this is unfair. I say that because I don’t believe (and never have) that there is any such thing as a stupid question. And to ask the question: What is Truth? appears to me to be a pretty good one. To ask that particular question sincerely is to open oneself to the more than obvious possibility that we don’t know all the answers.

And that brings me back to the word that Melville uses – Faith. It, too, can become familiar, like an old pair of slippers. It takes someone of the calibre of a poet or a novelist like Melville to pull us up short and ask us what we mean when we use the word. The poet throws in the bit of grit which makes those slippers feel a little less comfortable. Instead of describing faith in terms of metaphysics, Melville turns to the law of the jungle. He turns to the scavenger picking up the scraps. He adopts the image of the opportunistic hunter surviving among the dregs of life itself. Melville’s faith is not the cosy faith of the church or chapel, but the rougher, hard-bitten faith that is born out of genuine experience. Faith becomes then, not a pleasant feeling, or a quality to be admired or a trophy to be displayed on a pedestal. It is the means by which we survive or perish. Melville’s own upbringing may have contributed to this outlook, but regardless of any autobiographical slant, what he says chimes with me.

One of my many heroes, Søren Kierkegaard once wrote:

‘Faith is the highest passion in a human being. Many in every generation may not come that far, but none comes further.’

Faith cannot be anything but passionate. Less than that and it is mere polite interest in the subject known as God. Faith was never intended to be the window dressing of life, but its mainstay. Faith is its own raison d’etre. And our lives are the poorer when we try to tame that particular jackal.